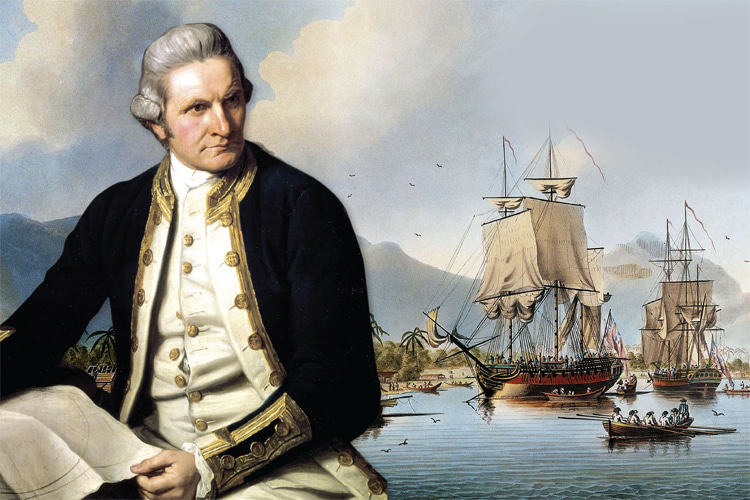

Captain James Cook (1728-1779) and his sailing crew are credited with writing the first-ever description of wave riding before surfing was even considered a sport.

James Cook was born on November 7, 1728, in Marton, Yorkshire, England.

He was a British navigator, explorer, and cartographer who served in the Royal Navy from 1755 to 1779.

Cook saw action in the Seven Years' War but became best known for the three voyages of exploration and scientific discovery made in the Pacific Ocean in the 18th century.

The first took place between 1768 and 1771 (HMS Endeavour pictured below), the second was held from 1772 to 1775, and the third between 1776 and 1780.

Captain Cook mapped the coast of Australia and New Zealand and paved the way for British colonization in Oceania.

In his voyages, Cook also determined there was no such thing as the mythical continent of Terra Australis said to have existed here.

He also helped to dispel the idea of a Northwest Passage, which the Old Continent had been obsessed with for centuries.

James Cook was the first European to describe Hawaii and one of the first to participate in the European colonization that settled in the Americas.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Europeans were obsessed with mapping and charting, and classifying the world.

And then, of course, as they colonized land, Europeans portrayed themselves as a civilizing force, bringing both science and religion to "primitive" regions.

In 1778, after failing to find a channel linking the Pacific to the Atlantic Ocean, Captain Cook and his 150-plus crew sailed HMS Resolution and HMS Discovery toward the southeast.

In early 1779, the sailors made contact with Hawaii. They had become the first Westerners to reach the archipelago.

The British were greeted warmly by the locals and spent three days ashore on the islands of Kauai and Niihau.

How Did James Cook Die?

The death of Captain James Cook is still not as clear as the waters of Hawaii.

One of the most popular and widely accepted theories involves Hawaiian rituals and religious beliefs.

In early February 1779, after a hospitable reception, Cook left the Pacific islands.

But the ship had problems and was forced to return eight weeks later to Kealakekua Bay for repairs.

The ships circled the Big Island. The Makahiki festival was underway. And natives were marching in procession from town to town.

Captain Cook decided to drop anchor in the north end of Kealakekua Bay (pictured below), but the Hawaiians interpreted the event as the return of Lono, the God of Fertility.

In the Hawaiian religious system, Ku - the God of War - rules for eight or nine months out of the year.

The other remaining months are reserved for the Lono.

The season festival for Lono is called "Makahiki." During the event, the Hawaiian king, who is associated with Ku, is ritually defeated.

During the Makahiki, an image of Lono tours the island, gets worshipped, and collects taxes.

At the end of the Makahiki period, Lono is ritually defeated and returned to his native Tahiti.

According to some historians, Captain James Cook might have been killed for a religious reason.

The thinking goes that because James Cook arrived in the middle of the Makahiki festival, Hawaiians perceived him as Lono.

So Cook took part in the celebrations and sacrifices and was killed as a ritual murder to mark the end of Makahiki.

For Ku to return and the regular political order to be restored, Lono had to be defeated and presumably killed.

Historians believe thousands of native Hawaiians paddled or swam out to the ships, captured Cook, draped in red cloth, and escorted him to a temple while onlookers chanted "Lono."

The British captain was then beaten, stabbed to death, and dismembered, with his entrails thrown into the sea and the remains burned and handed out to local priests and chiefs.

The Alternative Death Theory

However, this is not the only theory surrounding Cook's death.

In his book "The Apotheosis of Captain Cook," Gananath Obeyesekere debunks the myth that Western explorers were gods to native Hawaiians.

His work was conceived as a counter-argument to a theory proposed by Marshall Sahlins' 1981 "Historical Metaphors and Mythical Realities."

Sahlins argued that Hawaiians mistook Cook to be their god Lono because of the coincidental timing of his arrival at the time of their Makahiki festival.

They believed Lono had returned in the flesh, in accordance with prophecy. Obeyesekere says that's all bunk.

He says they knew he was a human - a chief of a sailing ship and came to know him as a nasty, murderous servant of the British Empire, so they killed him to stop him.

After he was dead, they gave him a burial fit for a king, following the local tradition.

The emeritus professor of Anthropology at Princeton University says the idea that Hawaiians believed Cook was Lono came from the European's own superior mentality.

They imagined themselves to be gods everywhere they were treated with South Pacific courtesy.

Obeyesekere says, "None of the new evidence substantiates Sahlins's thesis that the apotheosis of Cook is a Hawaiian rather than a European phenomenon; nor has he dealt adequately with the methodological criticisms that I made of his previous work, particularly those pertaining to source material."

In conclusion, Gananath criticized Sahlins' interpretation of Cook's death for looking a lot more like a European myth than like a Hawaiian ritual.

Obeyesekere also notes that the British ocean explorer would not easily be confused with Lono.

In fact, if he was mistaken for a God, it would probably be Ku, the God of War, with all the cannons and muskets.

Last but not least, Lono is associated with fertility, so the Hawaiians would have associated the Europeans with the opposite of fertility because they introduced gonorrhea to Hawaii.

The Cook-as-Lono theory has another problem in its equation - nothing in Hawaiian religion has gods being ritually murdered.

Part of Hawaiian mythology can be seen as the killing ritual of a king, but not of a god.

For many, Captain James Cook was probably killed during a melee.

Before his brutal death, the British sailor had attempted to take a Hawaiian king hostage in response to Hawaiians stealing Cook's ships.

Cook had already done the same thing in Tahiti and other Polynesian Islands after locals had taken his goods.

So, it is highly probable that Cook was killed because of tensions between Hawaiians and European sailors.

Let's not forget that these foreign English "visitors" dismantled a Hawaiian ritual space - maybe a temple - and used it for firewood.

Cook tried to compensate for the damage caused, but the offer of two hatchets was refused.

The theory that supports the idea of an enlightened, civilized European navigator and cartographer being killed in a primitive ritual is an argument that has always fit in the Western superiority complex.

So, the debate is open and may never be historically proven.

The World's First Description of Surfing

The first written description of wave riding appeared in a 1777 journal entry published in "A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean," a three-volume book series published after Cook's death.

Initially, historians believed that the famous passage had been written by James Cook himself, but the first-person voice is actually misleading.

The words were poured into a paper by Dr. William Anderson, HMS Resolution's surgeon.

Anderson was mesmerized by the board riders.

While his ship was anchored at Matavai Bay in Tahiti, the surgeon walked along the bay and observed the locals paddling their canoes and catching waves toward the shore.

Here's how he described the act of walking on water:

"I could not help concluding that this man felt the most supreme pleasure while he was driven on so fast and so smoothly by the sea; especially as, though the tents and ships were so near, he did not seem in the least to envy or even to take any notice of the crowds of his countrymen collected to view them as objects which were rare and curious."

"During my stay, two or three of the natives came up, who seemed to share his felicity, and always called out when there was an appearance of a favorable swell, as he sometimes missed it by his back being turned, and looking about for it."

"By then I understood that this exercise... was frequent among them; and they have probably more amusements of this sort which afford them at least as much pleasure as skating, which is the only of ours with whose effects I could compare it."

But, in an unprecedented turn of events, in 2006, historians revealed that Anderson had not been the first to document board riding in the Pacific islands.

Eight years before Dr. William Anderson's description, Joseph Banks, the resident botanist at HMS Resolution, had already written about the Matavai Bay wave riders.

Here's how he chronicled what he saw:

"(...) the shore was covered with pebbles and large stones; yet, in the midst of these breakers, were ten or twelve Indians swimming for their amusement: whenever a surf broke near them, they dived under it, and, to all appearance with infinite facility, rose again on the other side."

"This diversion was greatly improved by the stern of an old canoe, which they happened to find upon the spot; they took this before them, and swam out with it as far as the outermost beach, then two or three of them getting into it, and turning the square end to the breaking wave, were driven in towards the shore with incredible rapidity, sometimes almost to the beach; but generally the wave broke over them before they got half way, in which case they dived, and rose on the other side with the canoe in their hands: they then swam out with it again, and were again driven back, just as our holiday youth climb the hill in Greenwich park for the pleasure of rolling down it."

"At this wonderful scene we stood gazing for more than half an hour, during which time none of the swimmers attempted to come on shore, but seemed to enjoy their sport in the highest degree; we then proceeded in our journey, and late in the evening got back to the fort."

James King's 1779 Surfer Report

According to surf historian Matt Warshaw, "no description of surfing that followed over the next hundred years would match Anderson's lovely 'supreme pleasure' observation."

The author of "The History of Surfing" notes that "soon after, in 1779, the HMS Resolution's Lieutenant James King wrote a detailed but choppy two-page journal entry on board-riding," recalling an afternoon spent on the beach at Kealakekua Bay, shortly before Cook's death:

"The surf, which breaks on the coast round the bay, extends to the distance of about one hundred and fifty yards from the shore, within which space the surges of the sea, accumulating from the shallowness of the water, and dashed against the beach with prodigious violence."

"Whenever, from stormy weather, or any extraordinary swell at sea, the impetuosity of the surf is increased to its utmost height, they choose that time for this amusement, which is performed in the following manner: Twenty or thirty of the natives, taking each a long narrow board, rounded at the ends, set out together from the shore."

"The first wave they meet, they plunge under, and suffering it to roll over them, rise again beyond it, and make the best of their way... out into the sea."

"The second wave is encountered in the same manner with the first; the great difficulty consisting in seizing the proper moment of diving under it, which, if missed, the person is caught by the surf, and driven back again with great violence; and all his dexterity is then required to prevent himself from being dashed against the rocks."

"As soon as they have gained by these repeated efforts, the smooth water beyond the surf, they lay themselves at length on their board, and prepare for their return."

As the surf consists of a number of waves, of which every third is remarked to be always much larger than the others... their first object is to place themselves on the summit of the largest surge, by which they are driven along with amazing rapidity toward the shore."

"If by mistake they should place themselves on one of the smaller waves, which breaks before they reach the land, or should not be able to keep their plank in a proper direction on the top of the swell, they are left exposed to the fury of the next, and, to avoid it, are obliged to dive and regain their place, from which they set out."

"Those who succeed in their object of reaching shore, have still the greatest danger to encounter. The coast being guarded by a chain of rocks, with, here and there, a small opening between them, they are obliged to steer their boards through one of these, or, in case of failure, to quit it, before they reach the rocks, and, plunging under the wave, make the best of their way back again."

"This is reckoned very disgraceful, and is also attended with the loss of the board, which I have often seen, with great horror, dashed to pieces, at the very moment the islander quitted it. The boldness and address with which we saw them perform these difficult and dangerous maneuvers, was altogether astonishing, and is scarcely to be credited."

Between the late 18th century and the 19th century, only a few dozen descriptions of wave riding were published.

Warshaw states that only "British and American explorers, merchants, missionaries, and wealthy adventure-seekers" dedicated a few paragraphs to the outdoor practice.

Furthermore, there was some confusion about the name of the craft.

"Hawaiians referred to it as papa he'e nalu, or 'board for wave-sliding.' English speakers at first tried 'floatboard,' 'sharkboard,' 'broad-board,' and 'bathing-board,' with 'surf-board' first used sometime in the 1790s," wrote Matt Warshaw.

"The terms 'surfer' and 'surfing' didn't take until the early twentieth century, which replaced 'surf-swimming,' 'surf-boarding,' 'surf-bathing,' 'surf play,' and 'surf sport.'"

One of the first non-Hawaiians to try board riding was Chester Lyman, a Yale University scientist who visited Honolulu in 1846.

Back then, he wrote, he "had the pleasure of taking a surf ride towards the beach in the native style," finding the experience "swift and very pleasant."